The Bristol Bus Company started hiring black people. This was against the Race Relations Acts, which banned discrimination in employment and public places. The government of Harold Wilson had brought these acts in. These laws were intended to make public places more racially equal. However, discrimination continued.

a libel case against Paul Stephenson

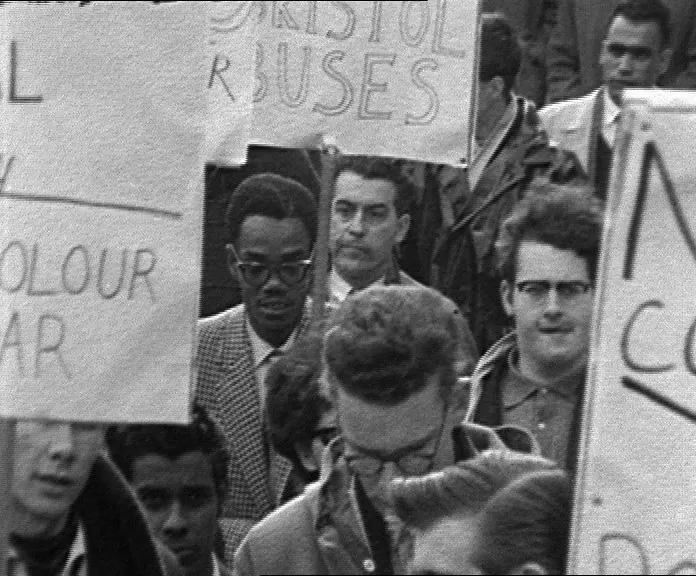

In the early 1990s, Paul Stephenson, a black man, organised a bus boycott in Bristol and was sued by the bus company. His actions were a reaction to the racial discrimination that was occurring in his city. He was a college educated man and the ideal spokesperson for his group. He also organised a test that proved the colour bar existed. This stunt attracted local media attention and prompted Stephenson to launch a libel case.

The libel case against Stephenson was launched in December 1963, just two months after the Bristol bus boycott. The libel suit was filed after Stephenson said that the white conductresses on the buses were not suitable for working alongside the black male drivers. The white bus conductors were accused of being militant and of not being able to work with black male drivers. Moreover, the Constabulary did not mix the races and the West Indies team refused to support the racial equality campaign.

The boycott lasted four months, during which time the TGWU and the Bishop of Bristol supported it. They also backed the local Black TGWU leader, Bill Smith. The campaign even attracted the attention of the high commissioner of Trinidad, Learie Constantine.

a race relations act

The Bristol bus boycott drew the support of the Labour Party and the Bristol Bishop in their campaign against bus drivers who discriminate against Black people. The boycott lasted for four months. Its supporters included Bristol’s West Indian Association, the Bishop and local Black TGWU member Bill Smith. High commissioner of Trinidad and Tobago Learie Constatine also met with the leaders of Bristol’s Labour Party and the TGWU. She urged the company, Transport Holding Company, to intervene in the protest.

The Bristol bus boycott inspired a new wave of social action in Britain. A group of young black activists in Bristol, including Roy Hackett, Owen Henry, and Prince Brown, formed the West Indian Development Council. They used the existing Afro-Caribbean community networks to promote their cause.

The Bristol bus boycott helped to lay the foundations for the 1965 and 1968 Race Relations Acts, which banned racial discrimination in public places, employment, and housing. These acts were the first anti-discrimination laws in the UK. Hackett and Bailey received OBEs for their work.

The Bristol bus boycott also prompted a significant influx of African and Caribbean migrants to the city. By the end of the decade, around 3,000 African and Caribbean people had moved to Bristol. This influx of immigrants unnerved some White communities in the UK. In the years following the Bristol bus boycott, race riots broke out in Notting Hill and Nottingham.

a libel case against West Indian development council

In the summer of 1967, the Bristol Evening Post published an article which exposed the city’s racism. The Bristol Bus Company’s management admitted that the buses were ‘coloured’ but blamed the Transport & General Workers Union. The TGWU denied this, but it was later found out that the Bristol Passenger Group had passed a resolution in 1955 against hiring colored people. Bristol bus workers were concerned about the impact of hiring immigrants, so they took action.

A statement signed by TGWU regional secretary Ron Nethercott and the Black West Indian Association’s Bill Smith condemned the Bristol bus boycott and called for quiet negotiations. It also condemned Stephenson, saying he was causing “harm to people of colour” and that the protest would ruin Bristol’s racial harmony. The statement was supported by the Bishop of Bristol.

The boycott drew national attention to the problem of racial discrimination in Britain. It was backed by national politicians, churches, and the High Commissioner of Trinidad and Tobago. It helped lead to the passage of the Race Relations Act in 1965 and the extension of its prohibitions to employment.

While the Bristol Omnibus Company had sought to resolve the dispute peacefully, the Bristol Bishop put pressure on Bristol Labour leaders and the Trinidad and Tobago High Commissioner to pressurise the Bristol Lord Mayor to intervene. The Bristol Omnibus Company also stepped in, and the company eventually declared that racial discrimination would no longer be tolerated in their buses.

a libel case against Dr Martin Luther King Jr.

The New York Times published an ad requesting contributions to defend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. against perjury charges. Although the ad was inaccurate in certain ways, the content was still deemed libelous. A political activist from Alabama filed a lawsuit, claiming the ad made false statements about his character.

While the decision was a setback for King, it was nonetheless a victory for free speech. The court ruled that the paper could continue to publish the ad. This decision paved the way for the civil rights movement. In the long run, the case will help protect the press and the First Amendment.

The advertisement in question featured the names of 64 people. Many of these were noted leaders and activists in the arts and public affairs. Four of them were individual petitioners, while 16 others were clergymen from different Southern cities. The advertisement also named King as a signatory.

Libel cases against public figures are difficult to bring. In order to win, the plaintiff must prove that the newspaper acted with actual malice in publishing the false statement. It is not enough to claim an innocently published statement. The newspaper must have known that the statement was false.

The lawsuit also involved the Alabama state government and a local Montgomery city commissioner. The ad was controversial and included the names of prominent civil rights activists.

a libel case against Bishop

After the Bristol bus boycott, the Bristol Evening Post published an editorial criticising the boycott. It pointed out the TGWU’s opposition to the apartheid system in South Africa and questioned what the trade union leaders were doing to combat racism in their ranks.

The Bristol boycott was the first in the United Kingdom to focus on race, and the black community took it upon themselves to initiate the boycott. In fact, the Bristol boycott spawned the first anti-discrimination laws in the UK. While the Bristol boycott failed, the Montgomery boycott was successful, partly because it targeted African-American bus operators. The intention of the boycott was to create propaganda and shame the government.

Although the Bristol bus boycott was a local issue, the TGWU regional secretary, Ron Nethercott, was the most powerful man in the West Country. His refusal to serve black passengers led to a yearlong boycott. The bus workers were, however, not motivated by colour prejudice, but by a fear of their incomes dwindling. The basic bus wage in Bristol, which was the same as the wages for skilled workers in the British Aerospace plant, was remarkably low.

After the Bristol bus boycott, the Bristol Bishop tried to negotiate a settlement with the company’s minority employees. He worked with the Lord Mayor and a Trinidad and Tobago High Commissioner to bring the dispute to a conclusion. During a mass meeting, 500 bus workers voted to end the colour bar and the Bristol Omnibus Company later announced the end of discrimination.

an end to the bristol bus boycott

In 1963, Guy Bailey, a young black man, was turned down for a job interview by the Bristol Omnibus Company. His manager said: “We do not hire black people.” This discrimination was well-known in the city, but it was legal. Guy’s protest drew inspiration from the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott, in which Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white passenger. After four months of protest, the Bristol bus company relented. This was an important step in the development of laws against racial discrimination in the UK.

The Bristol Omnibus Company’s colour bars effectively banned black people from front-line positions. The company claimed that Black people’s work quality was inferior. This discrimination fueled a racial backlash that pushed the Bristol bus company to change their policy. An end to the Bristol bus boycott was eventually achieved in April 1963, after the Bristol Omnibus Company changed its policy.

The company’s decision to reinstate black drivers was met with opposition from the Bristol Labour Party and local media. Some Labour Party members compared the colour ban to apartheid. The West Indies cricket team also refused to publicly support the boycott, saying “sport and politics do not mix”. The issue was covered by both the local and national press for several months. Even the Bishop of Bristol refused to support the boycotters, citing the issue of racial equality.

The Bristol Omnibus Company’s decision to end the colour bar policy was the result of negotiations between the union and the Bristol Omnibus Company. The union met with 500 bus drivers on 28 August 1963, the same day that King spoke at the Lincoln Memorial. It is a sign of how the Civil Rights Movement had reached the British shores. The Bristol Omnibus Company also made history by hiring a non-white bus conductor, Rahbir Singh.